John L Clarke, wood carver

John L Clarke, wood carver

The Man Who Talks Not – by Dana Turvey

Published Flathead Living Magazine, July 2007

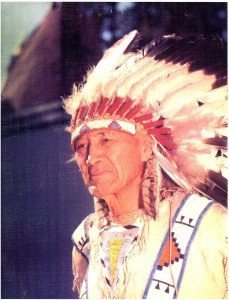

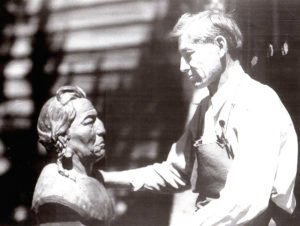

Throughout his long life, John Louis Clarke used his hands to express his words, and even more magically, he spoke through his exquisite carvings of Montana’s wildlife. Born in 1881 to a Scottish/Blackfeet father and the daughter of a Blackfeet chief, Clarke was a deaf mute from age two. But Clarke was lucky; the bout of scarlet fever that claimed his vocal cords also took the lives of five brothers.

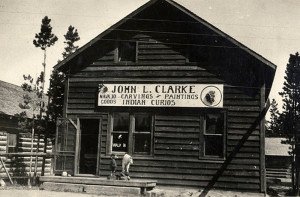

After a few years training at deaf schools and art institutes, John Clarke settled in Midvale, which would become East Glacier Park. There, in his rustic studio, he spent his days carving the images he loved. He was also an adept painter, working mainly in watercolors. Although far better known for his wildlife portrayals, Clarke never strayed far from his Indian roots.

Even President Warren Harding displayed a Clarke eagle holding the American flag in his Oval Office. In his lifetime, John’s precise carving received numerous awards; the 1941 edition of Who’s Who in Art says he was ‘generally considered to be the best portrayer of western wildlife in the world.’

Said John Clarke himself, “I carve because I take great pleasure in making what I see that is beautiful. When I see an animal, I feel the wish to create it in wood as near as possible.”

Said John Clarke himself, “I carve because I take great pleasure in making what I see that is beautiful. When I see an animal, I feel the wish to create it in wood as near as possible.”

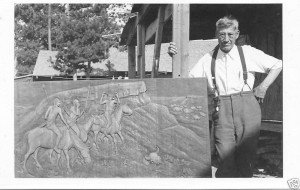

In 1940, Clarke turned his energy to carving enormous wood panels depicting the life of the Plains Indians. Weighing in at one ton each, two panels line the lobby of the Blackfeet Hospital, while a smaller third panel adorns the entry of the Museum of the Plains Indians, also in Browning.

In one scene, a white man and Indian are posed while sharing a peace pipe, with traditional teepees and ponies in the background. A second relief shows mounted Indians running buffalo over a cliff, while the third is a striking showcase of three braves praying to the sun.

His best-known wood panel is on permanent display at the Montana Historical Society, titled ‘Blackfeet Encampment.’ Like a great storyteller, Clarke used the frieze to portray Indian life, which is said ‘to capture the essence of the tribe.’ Carved from cottonwood, this panel measures 13’ x 4’ and proudly adorns the museum lobby in Helena.

At age 37, Clarke made another effective career move, marrying Mamie Peters Simon, who would use her business sense to manage John’s art career. In their fifties, the couple completed their family with the adoption of their young daughter, Joyce.

“My mom was the one who made it into a real business,” recalls Joyce Clarke Turvey. “My dad just wanted to make carvings, and a couple times, if someone complimented him, he’d just hand it over as a gift. Mom did much to promote my dad’s work and take care of the details.

“My mom was the one who made it into a real business,” recalls Joyce Clarke Turvey. “My dad just wanted to make carvings, and a couple times, if someone complimented him, he’d just hand it over as a gift. Mom did much to promote my dad’s work and take care of the details.

“Every year, he’d go to the Great Falls Fair to carve; these he sold for $1.50 to $10, depending on the size. I never went with him, but each summer I looked forward to the trip, because I knew my dad would bring home a doll or some sort of new toy for me.”

Compare those prices to a recent sale, when a collector paid $2,000 for a small 3” high bear carving, typical of Clarke’s favorite work. Mountain goats and bear were the images the wood carver was most drawn to, perfected by his time spent hunting and fishing.

John’s daughter remembers, “He was just a great fisherman…friends used to say that he could just drop a line in the water and he’d pull up a fish. And he hunted quite a bit – I grew up on venison and elk meat.”

As a tribal member and ¾ Blackfeet himself, Clarke headed to Indian Days in Browning each year. Though deaf, in that era many tribesmen knew Indian sign language, and the artist used the celebration as a time to catch up with friends and socialize with something other than his fishing pole.

Joyce adds, “Even into his 80’s, he’d walk into town to check his mail and have lunch at the diner. He spent so much of the days sculpting that it was a good break for him to get away each afternoon. To the time he died, he had so many orders for carvings, but he had cataracts in both eyes and such arthritis in his hands that he couldn’t meet all the requests.”

Joyce adds, “Even into his 80’s, he’d walk into town to check his mail and have lunch at the diner. He spent so much of the days sculpting that it was a good break for him to get away each afternoon. To the time he died, he had so many orders for carvings, but he had cataracts in both eyes and such arthritis in his hands that he couldn’t meet all the requests.”

Over the years, while Clarke was carving a place for himself in art history, he was also inspiring other Indian artists. Fellow Blackfeet who carried the torch are sculptor Albert Racine, illustrator Gerald Tailfeathers and painter Victor Pepion.

In 1993, the Montana Historical Society ran a special year-long exhibit of Clarke’s work. At that time, curator Kirby Lambert told the Great Falls Tribune, “To those who knew him, John Clarke is most often recalled as a kind man with a warm smile and strong hands, whose silent presence made a trip to Glacier just a little more magical.”

Even though he lived in a silent world, Clarke was able to express himself, showing off his famous sense of humor – more often than not, he’d be found laughing and telling tall tales of his adventures in the wilderness. Right up to his death at age 89, the artist continued to spend each day creating the creatures of Montana’s wild.

Even though he lived in a silent world, Clarke was able to express himself, showing off his famous sense of humor – more often than not, he’d be found laughing and telling tall tales of his adventures in the wilderness. Right up to his death at age 89, the artist continued to spend each day creating the creatures of Montana’s wild.

Recently, Lambert added, “Many people have praised Clarke for his ability to perfectly replicate animal anatomy, and he could certainly do this. In my opinion, however, his true gift lay in his ability to go beyond this accurate replication of animal forms, and instill in each and every carving its own distinct personality and sense of liveliness.”